Eric Brown is a Yuin, Gundungarra man born and raised in La Perouse,

Sydney in the local Aboriginal mission with his mother and three siblings.

He witnessed domestic violence in the streets, alcohol abuse, exposure to heroin users and overdoses, and watched peers entering and reentering custody. “Luckily, I had a mother who was extremely caring who made sure I attended school, participated in football and stayed out of trouble,” he said.

He completed his HSC and held various jobs in the construction industry, landing a fulltime role as a water proofer where he stayed for eight years. During this time he played for La Perouse at a local level in South Juniors competition and represented South Sydney Junior Rugby League Club in the Harold Matthews’s cup, SG Ball and Jersey Flegg teams. He joined the Western Suburbs Devils in the Illawarra Carlton League, representing Illawarra Country.

An offer to play for Moranbah Miners football club in Mackay, North Queensland came along, and he got full time work in the mining industry earning $150,000 a year. He played in and won his last Grand Final with the club that year and, in his words, was “on top of the world”. He made long term plans with his brother to buy their first home.

On October 16, 2011, while playing in the Aboriginal knockout Rugby League competition in Cairns, when five minutes into the second half, the other team scored a try. “They were screaming and celebrating in our faces, and anyone who knows me, knew this would piss me off,” he said.

“The trainer asked me to come off for five minutes for a rest and I told him I was going to smash the next guy that runs it before I came off and proceeded to the kick-off. In a tackle that I’ve done off the kick, over and over again, everything went right for it to go wrong.

“As I went in to get under the ribs of the other player, he stepped slightly, lifted his leg and copped his knee into the left side of my neck. I was lying there a bit dizzy and realised my arm was not working but thought it was just a stinger. I was walked off the field in a jelly like state not feeling the best.”

He sat on the bench for five minutes waiting for his arm to come back but nothing happened. “I waited another 10 minutes and realised that this was a lot more serious to what I first thought. I was then walked over to the medic table where they tried to settle me and see where I was at but the pain worsened.” Shortly afterwards he was taken to Cairns hospital in an ambulance.

Reflecting on this time Brown recalled not feeling too bad after receiving morphine for the pain, however, as time went on the pain set in, describing it “like someone was trying to pull my skeleton out of my body”, with throbbing pain from the tip of his toes to the tips of his fingers, and into his head. “After being administered the largest amount of morphine possible I was able to fall asleep but when I woke up the next day my body was stiff as a board, and I struggled to move.”

As a result of a blood build up between his spinal cord and vertebrae his body had shut off for a short time. “I thought to myself what the f… have I done here”.

Because doctors were unable to treat his type of injury, but only manage the pain, Brown was transferred by the Royal Flying Doctor Service to Royal North Shore hospital in Sydney where he stayed for four months being monitored with concerns about meningitis.

He had sustained a brachial plexus injury, tearing the C5, C6 and C7 nerve roots completely out of his spinal cord which ran his left arm, leaving the arm completely dead. After four surgeries including a nerve graft, with muscle moved from his forearm to his bicep, stem cell treatment and his wrist surgically fused in place, he has regained limited use of his left arm. However, he has been left without tri-cep muscle function, no peck muscle and or muscle function to open his left hand.

But it was following discharge from hospital when reality hit. He was living with his mother in La Perouse, without a job, and told by doctors be would never play football again and with the use of only one arm, his future looked uncertain. And with this uncertainty came a deep depression.

He admitted that while not reaching a point where he wanted to hurt himself, he was down there. “I began drinking every day, taking whatever drugs I could get my hands on, and doctor-shopping to get as much of the drugs to help relieve the mental and physical pain I was going through.” This drug and alcohol addiction went on for two years.

In 2014 he rediscovered his competitive drive and started training at CrossFit Kia Kaha gym losing over 20 kg. Fast forward to 2019, and he is a member of CrossFit Inventive in Caringbah, Sydney, and recently competed in the WheelWOD open worldwide, the equivalent of the CrossFit Games but for adaptive athletes. He was placed eighth in a top 12 finish out of 40 athletes worldwide and invited to represent Australia in Minnesota Vikings stadium granite games and Canada in the 2021 seasons against the top 12 in his division, although, due to the current Covid situation travelling overseas is uncertain at this stage.

“This is a big achievement for me, not as the only Australian in my division, but the first Aboriginal man to compete at this level in Crossfit,” he said.

Brown has been a caseworker with Youth Justice since 2016 in an Aboriginal Practice Officer role teaching Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal staff how to work, with and develop practice and programs for young people with high needs in the justice system.

“I love helping our young people stay out of custody and getting them on the right track delivering cultural interventions and programs in custody on a weekly basis.I can also be a role model in my chosen sport to compete in a worldwide CrossFit competition,” he said.

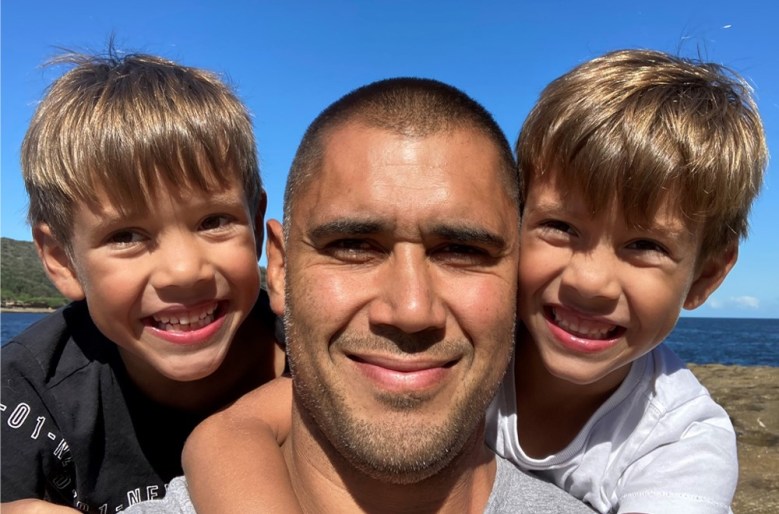

“I now have a family of seven, a proud partner and father to five young boys, aged from 15- months to 14 years, including 6-year-old twin boys.”